On pyschogeography. Without enthusiasm.

Psychogeography is a term used to describe places in a way that acknowledges how we experience our environment does not chime with its tangible reality. Our mental maps and pictures of a place might foreground memories and histories, emphasising familiar and personal routes and landmarks and often embellishing them with myths and patterns.

We are free to go as far as we want when speculating on what might lie over the metaphorical hill. Hence fantasy and science fiction, which encourage our imaginations to trespass beyond the constraints imposed by our anthropocentric ideas about reality and time.

In essence, Psychogeography seeks to substitute a canvas of fragmented impressions for the simplified vision of a two-dimensional map, exploring the borderland between the real and the imagined.

Frankly, I do not like the term. It seems intellectually pretentious and its self-appointed practitioners are sometimes too keen to pass off what is clearly entirely imaginary in place of stories that reflect lived histories and experiences. It is obvious that the patterns, colours and figures on the canvas of London in my head, will be different to those in yours, not least because our experiences and perceptions vary. The question for me is, while acknowledging that, how far can one move away from the kaleidoscopic but solid reality of the City and city life, without going way beyond description and into fiction and abstraction. In looking for colour and complexity, they throttle any hope of describing the lived experience of the city.

Two-dimensional maps are indeed problematic. We are often reminded not to confuse them with the territory they seek to represent. Labels and boundaries are arbitrary impositions. The symbols and lines in an OS map do not appear on the ground; you don’t find the dotted lines marking a path or boundary on the earth under your feet or find that churches with spires are usually circular.

Nonetheless, they are influential. Many people think that the shape of London and the distances between tube stations are indeed as depicted in the tube map, and rank landmarks as important simply because they are marked on Google Maps. Mercator's map of the Earth is a classic example, created to interpolate the globe onto a flat map. Greenland is under 8% the size of Africa. In Mercator's projection, it is a similar size.

How do we make sense of our physical world?

Starting from the beginning. We are all familiar with mental mash-ups of real and imagined places. Witness any number of creations from William Blake’s ‘Jerusalem’ to Harry Potter’s Diagon Alley, the concrete horror of Ballard’s ‘Crash’, Jerry Cornelius’ Ladbroke Grove as urban noir, Victorian gloom in Dickens or the colour-washed Edwardian setting of the Mary Poppins films. These can impinge on the real world; witness for instance the shopping cart stuck in the wall of Platform 9 ¾ at Kings Cross Station or Little Dorrit’s Stairs next to London Bridge. I once went to Woking simply to see the place where the Martians attacked in H.G. Wells 'The War of the Worlds'.

Each one of these simply asks us to view the City through a different coloured lens, usually playfully or simply to create a mod or make a point. Few of us take any of it too literally. It is a bit like that moment in the old cartoons when Wile E. Coyote runs off the edge of a cliff and then keeps going for a while. It is unbelievable. We know he is going to plummet but, just for a while and for entertainment’s sake, we suspend that disbelief.

In contrast, the doyens of literary urban psychogeography like Iain Sinclair and Peter Ackroyd, particularly in their books, are asking more of you. The city itself is the foreground rather than the background for their narratives. They are serious and their aim seems to be to superimpose a layer of faux, mystical antiquarianism and cabbalistic innuendo onto the cityscape and its attested history. By submerging you in it, they make it the point of the performance rather than the backdrop. Rather than inviting you to take a ride on a ghost train, they want to engage you in their séance. And to what end?

I guess that in the tech world, this is the point at which you tiptoe from augmented to virtual reality, from Pokémon Go to one of the games made for an Oculus headset. Don’t get me wrong. I like some of Sinclair’s targets and regret the rationalising and sterilising character of much new development. But these pseudo-scientific occult analyses of the City stretch my credulity too far, daubing greasepaint onto the face of a reality that is in truth far less engaging. But I don’t need to believe in ghosts to enjoy a ghost train, or ley lines and underground worlds to savour the City with its memories, medieval mazes and bizarre bazaars.

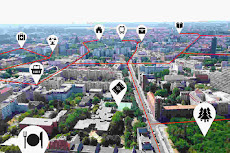

There is a sub-branch of academia (if the Dept. of Education hasn’t already starved it to death) called behavioural geography. Within it, the concept of ‘mental maps’ recognises the relevance of the reflexive mix of objective knowledge and subjective perception we use in navigating our way through the physical world. The photo-map below illustrates this, showing the layout of part of Berlin as understood by immigrants. The intention was practical and insights like this have helped urban designers demonste that it is quite possible to sashay from the map to the territory without reinventing the latter. Mind you, I still can’t find my way around the Barbican and get disorientated in monstrosities like the Westfield Shopping Centre.

|

| The Immigrant's-eye view of Berlin |

There is a river of European thought that flows alongside all this and at this point, if you are not familiar with the cast of characters, I can only ask you to accept that they have a role in the play.

Continental 'psychogeography' has a different flavour; less pretend science and more ideology. One root was Baudelaire’s idea of the ‘flâneur’, a strolling, detached observer of city life, usually Paris. Aspects of this were embraced by both some of the pre-war avant-garde art movements and eventually inherited by the ‘Situationist’ movement in turbulent 1960s France. They saw it as subversive and it became first and foremost a political project rather than an artistic statement.

The root of the idea was that, by becoming obsessed with the consumption of material and immaterial goods (Fast Fashion and Netflix if you want) we disengaged from the direct experience of life. It became banal. This was a popular notion among political philosophers at the time, particularly those reinventing Marxism. A frontrunner was Guy Debord who embraced psychogeography as a means of undermining the expectations and canalisation of urban life. (He actually suggested that this could be done by a ‘technique of transient passage through varied ambiences’. I can only hope that sounds better in French).

|

| Guy Debord |

If you are interested in all this theory, the Wikipedia entry is quite well written. [ Link ]

This is my second gripe. Surely, when it comes to confronting the evils of capitalism, psychogeography in the hands of a bunch of political and artistic radicals is about as much use as a feather duster in a coal mine. And if the immediate target is to address the alienation that is intrinsic to consumer capitalism, then the flaneurs, who are detached observers, are surely themselves alienated. In their mind's eye, they place themselves at the hub of the wheel of the city, but because they are not an integral part of it, they have become part of the problem. It isn’t so much a ‘transient passage’ as an ego trip.

Hence Pootling. To me, the word carries the same notion of unhurried and unfocused exploration; but it does so without any of the associated intellectual hype or political baggage. As an activity, it won’t change the world. It is an entertainment. Personally, I don’t need the psychogeographer’s colouring book to experience the intrigue and wonder of a City like London or the joys of the surrounding countryside. It isn’t necessary to intellectualise or re-imagine it. The reality, with its rich depth of history and people, speaks for itself.

|

| More Banksy |

I'd say the genre it 'literary' rather than 'geographic' - something closer to poetry than science. Yes I think people are projecting their views onto the landscape, and this will include social and political prejudices.

ReplyDeleteLiving in the City of London I am able to draw on the ancient myths of Boudica, the underlying Roman city, the freemasonry in the City as well as the financial and ethical legacy of colonialism.

I very much enjoyed reading Ballard, Ackroyd, Will Self, Alan Moore etc.

When I said above 'more like poetry' I was thinking of something like Wordsworth's Tintern Abbey - a set of impressions inspired by the landscape, and I think this is what the psychographers are doing, although the mythology will only appeal to some.