On the seventh day, God rested. He put his feet up, had a beer and took his eye off the ball. Chaos ensued.

Geology is the study of pressure and time. That's all it takes really, pressure and time. (Red: The Shawshank Redemption)

This is about the landscape of the northern Home Counties. Nothing of early Earth can readily be seen in them, but I thought that I ought to start at the beginning and acknowledge the canvas before asking you to admire the painting. There are two big things that you need to be aware of. Everything else is detail.

As I am sure you know, it all started with the Big Bang some 14bn years ago which, initially at least, wasn't big and wasn't a bang. If you want an explanation, try this short video: Link : Big Bang . In any event, it wasn't until 4 billion years later that there was a proto-Earth.

This would have been a hellish time to visit. Early Earth lacked a magnetic shield to protect it from the nasties that the sun was spewing out, and an atmosphere to shield it from the rain of meteorites. Atmosphere makes a difference; take a look at the moon now and see the craters. Ouch. It was very much closer then, so its gravitational pull was greater. This, combined with the Earth rotating every five hours or so, triggered tsunamis of molten lava, sloshing across the planet's surface.

|

| The 'Hadean' period on Earth. Don't go there. |

Then, slowly, it started to cool. A crust formed on the surface and fractured into giant slabs, which over time became the 'tectonic plates' on which our continents formed (we are not sure how) and ride. These started to shift and slide around on the more viscous, deeper layers. When the plates clashed, they buried, or got buried, by each other.

The Earth is restless and an enthusiastic recycler. We still don't really understand the dynamics, and no legacy of all this can be seen locally. Those plates changed a lot and travelled a long way to get to where they are today.

|

| The Early Continents |

The diagram below illustrates how complicated it all is. Credit to the Encyclopaedia Britannica Kid's Edition, which is about my level. I know that you can't readily make out the details on a phone, so if you are interested, you can find the original using this link: Tectonic Chaos

As the continents on their plates drifted around and collided, they created oceans and troughs, mountain ranges, earthquakes and volcanoes. Those oceans and mountain ranges came and went. When land sank below the surface, thick layers of sediments gathered on top of it, only to be eroded away when it rose to the surface again. Nothing stayed put. Nothing stayed the same.

The result was that yesterday's ocean floor might well have ended up on a hillside miles from the sea, and today's mountains will one day be seabed. Our own area has bobbed up and down like a yo-yo. It still does, just very, very slowly, sinking at about 1mm a year relative to sea levels, which, as you know, are rising for other reasons. Don't throw your wellies out.

It didn't help that changes in the atmosphere's chemistry periodically switched the planet from being a freezer to a greenhouse. Early 'global warming' might have been down to huge volcanoes vomiting carbon dioxide on a scale which produced an early atmosphere, which was protective if unbreathable. Oxygen appeared later, probably minted by bacteria in the oceans, while subsequent changes in the mix of gases further exacerbated the rise and fall of the sea levels. A lot. This all had a profound and generally negative effect on the career plans of early lifeforms. Few survived their redundancy notices.

If you want to make sense of all this, you need to factor in the timescales involved. With our perceptions constrained by our senses and eyeblink life spans, these are unimaginable. So I will now ask you to imagine them.

At the moment, your current perch is moving away from America at about the speed at which your nails grow. That might not sound much, but over, say, ten million years, which is just an eyeblink in geological time, America would be 200 km away. The vertical hold shifts as well. The Himalayas are currently rising by around 1 cm a year because the tectonic plate carrying India is bashing into Asia. The highest point in S.E. England at 300m is Walbury Hill in Berkshire. At that rate (and if some of that increase wasn't being eroded away), you could add something that height in just 30,000 years. I have known slower building lifts!

In short, there is no chance that an underpowered dilettante like me could cram 4bn+ years of history into a short, linear and comprehensible blog post, given the time scales and number of violently interacting forces at play. In any event, but no shadow of it falls on most of the natural landscapes in our area anyway, so there is nothing to be gained by squinting too hard through the geological time-telescope.

If you want to see really early stuff without travelling afar, you have to travel to North West Scotland, perhaps.

This all sounds very dry even as I write it. It is, after all, paleogeology. Maybe I could sex it up with some 'saucy postcard' style innuendos about bumping and grinding, eruptions and maybe even subduction? Then again, maybe not.

The curtain closes on this first Act in our tale, some half a billion years ago. At that point much of the surface of the planet was submerged beneath vast oceans and land was concentrated in the Southern Hemisphere and, finally, beginning to develop some of the soil cover that would support plant growth The bits that would one day do a 'reverse Atlantis' and rise above the waves to become South East England, were part of an ancient sub-continent rather beautifully named 'Avalonia', tacked onto a bigger land mass called Gondwana and floating about down near the South Pole.

|

| Earth, 450m BC |

The atmosphere was at last relatively breathable, and Earth had also gained a magnetic field which protected it from the Sun's most beastly rays. Life was springing to life. Initially, it was just microbial speed dating. Then the seas filled, initially and mostly with very small and simple creatures pootling (!) around amid some weird and wonderful fauna and flora. By the end of the period, a myriad of bizarre creatures were emerging from nature's skunk works. I love David Mountain's description of them as 'Pokémon designed by H P Lovecraft'.

The end of this First Act in the show was a mass extinction. There will be several of these, and it appears that this one was down to global warming. (Take heed!) Most living creatures copped it. If they hadn't, you might now look more like one of the monsters from Dr Who.

At the very end of this early period, Avalonia crashed into another early continent, Laurasia. Scotland was piggybacking on the latter. The result was the joining of what became England and Scotland, along a line between what is now the Solway Firth and Berwick. Today's border follows that line, and everything you were taught at school about the two countries being joined in the Act of Union in 1707 is pure misinformation.

|

| The Anglo-Scottish Border now |

What is left of Avalonia now lies deep in our regional basement, hundreds of metres below the surface. Our bit of the planet was underwater.

The sad fact is that, while the wonderful Nordic stories about a world of ice and fire are spot on, the rest of the stuff about immense Ash trees, ice giants and enormous cows isn't actually attested by science. More's the pity. If this disappointment is too much to bear, take a look at this really good interactive graphic showing the changes through time.

The good news is that the upside of all this is that Britain's strange path, wandering around the planet, submerging and emerging and often ending up on the liminal edges of early continents, has left Britain as a whole with richly varied geology and some wonderful and unique landscapes. The chalk lands of the South East are among them.

|

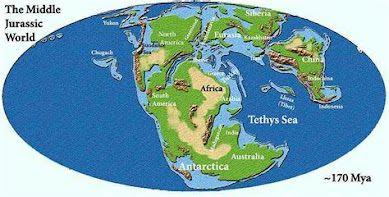

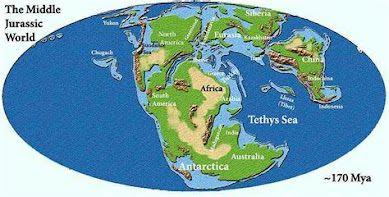

| Jurassic Geography |

As we get into a bit more detail, please don't forget that I am not a paleo-anything but rather a recreational scribbler indulging in a heroic degree of generalisation in a quest for simplicity.

The pic above is a map of the world in the Jurassic, a period named after the film. If they ever make a documentary about the Age of Dinosaurs, the opening and closing credits should be set against two massive extinction events which, like their forerunners, comprehensively shuffled the cards in life's game of chance, but never quite finished it. The first and greatest was at the start, perhaps 250 million years ago. Most life on Earth disappeared. The cause was volcanic activity, causing an increase in carbon dioxide, i.e. global warming, but it wasn't us; we have an alibi and were simply not around to try the DIY version.

In the background, land masses continued to shuffle about. New lifeforms appeared, both in and out of the water. The Earth still had two great continents, Gondwana, which I have already mentioned, and Laurasia. They were separated by the beautifully named Tethys Sea. Wouldn't it be great to get the job of naming this stuff? In Greek mythology, Tethys was a Titan, the wife of Oceanus and the Goddess of Fresh Water.

|

| Tethys |

As you can see from this contemporary picture, she had wings growing out of her head. Frankly, judging by the fashions of that period, that probably wouldn't have been thought weird. For instance, take a look at the way that the Triassic reptile below carries his golf clubs. Evolution plays strange tricks.

|

| Longisquama |

As the world continued its recovery, what was left of that Carbon Dioxide ensured that the climate was warm and the polar ice disappeared. Sea levels rose and again covered a lot more of the planet, as you can see from the map. The first birds had taken to the air, and a few small and rather odd mammals appeared. You might even see some plants that would look familiar to gardeners today; the ancestors of ferns, conifers, ginkgoes and Yuccas. There was no grass. None. An odd thought.

About 230 million years ago, probably on a wet Monday in March, Dinosaurs turned up. They were indeed big beasts: Titanosaurs, Megalosaurus, and Iguanodons. But T Rex and his pals, as portrayed in the Jurassic Park film, actually only emerged on the scene in the Cretaceous (or chalk) Period, which came later.

In fact, more time passed between the first dinosaurs and T Rex than between T Rex and you. Hollywood lied to you; nothing new in that, but did you know that their deceits didn't stop there? The dinosaur sounds in Jurassic Park were just amplifications of the noises that Tortoises make during sex. Honestly!

|

T Rex. Circa 1970.

Sorry. Couldn't resist it. |

By this time, our bit of the Earth's crust had wobbled northwards and was perched around the latitude of modern Morocco. It was part of the islands and shallow seas in the 'Eurasia' bit in the upper middle of the map of the globe at the top of the post. The Jurassic Coast Visitor Information Centre in Dorset had yet to open.

Those shallow seas would have teemed with life. As well as Monsters Of The Deep, there were vast, vast forests of glass sponges and countless corals and tiny creatures, many comprising only a single cell which, on dying, sank to the seabed. And of course, the oceans and lakes were also full of the usual sea muck, sand, gravel and the river-borne debris of the ever-eroding continents.

The end of the Jurassic was protracted. Again, vulcanism was partly to blame, but it, in turn, was partly caused by the restless planet breaking up those large continents, Gondwana and Laurasia.

|

| Nemo wouldn't have stood a chance! |

The Cretaceous period was fiery, hot and wet. The three are related. Fiery, because those massive volcanic eruptions continued, Gondwana did not just quietly disintegrate. That again led to more carbon dioxide and warming, which in turn melted the ice caps and led to sea levels rising up to 200m. After a while, it was a blue planet with little land left. What there was, was mostly covered by fairly open forests of ferns and coniferous trees. So not really a jungle, and offering some easy hiking. But if you visit, take some oxygen and very, very good insect and dinosaur repellent.

This brings me to the point of this post, namely the creation of the rocks that form the countryside of South East England and which you can sit and picnic on, or even brush your teeth with. Britain is a geologist's paradise, with variety coming from having drifted around the world, forming from the flotsam of broken continents. Our bit in particular spent a lot of time under that sea, where aquatic ooze, compressed under the weight of the ocean above it, morphed into the rocks that lie deep under London itself today, but which come to the surface in the hills that surround it.

There are four main types hereabouts: limestone, sandstone, chalk and various mudstones. Each was laid down as the ocean floor at different times and in different places from different mixtures of the ooze. Hereabouts, the Limestone of the Cotswolds is mostly Jurassic, while the sandstone ridges and the layers of chalk of the Chilterns and Downs were laid down successively in the Cretaceous (i.e. chalk) period, which came next. Mudstones can be relatively recent.

You might wonder how there was ever enough compressed ooze to create hills. The answer, once again, lies in the unimaginably long timescales involved. If you piled up sheets of paper for ten million years, you would have a pile several times higher than the highest point in the region. And that is only a passing moment in geological terms.

|

| Antarctica in the mid-Cretaceous period |

I want to talk a bit more about these rocks because they have an immense influence on our landscape But these posts are created to be read on phones, so I don't want them to get too long. So I will cover them later in the series.

To finish, what follows now are what one of my sources describes as ‘penecontemporaneous palaeogeographic’ events. Save that one for your next Scrabble game!

By the end of the Cretaceous period, temperatures and sea levels were falling again, and the seabed and the sediments heaped on it were uncovered. It was still being mangled by the slow but never-ending and violent movements in the Earth's crust, but the flotsam and jetsam of broken continents, floating around northern seas, were morphing into something recognisable as Britain.

Once rising and exposed, the new land started to be viciously shredded by rivers and eroded by wind, rain and chemical solution. Much of that eroded material ended up as clay and mud. If there is one thing omnipresent in the last billion years on Earth, it is mud. And since this process has been going on forever, at different rates in different places, some clay pre-dates the rocks we find, and some was formed later.

The coda to the Cretaceous was yet another great extinction. This one is usually ascribed to an asteroid the size of Luton crashing down in what is now Mexico, shattering the Earth's crust, creating huge tsunamis and blanketing the planet with soot and dust. Other theories are available. Whatever, years of darkness ensued, and acidic rain poisoned what wasn't killed by the loss of sunlight. The result was that 75% of all species of life on Earth vanished, notably the dinosaurs and ammonites. We move on.

|

| Oh no! It's Luton. |

If you are actually interested in this stuff, I have two suggestions for books to read. Neither is difficult or technical, and both are colourfully written. Sadly, neither author remembered to take a camera into their time machine.

'Otherworlds' by Thomas Halliday, describes what you would have seen and found if you could do a bit of time travelling back through the epochs.

'Vanished Ocean' by Dorrik Stow is about the birth and dwindling away of what was once one of the greatest Oceans on early Earth, the Tethys Sea.

There are also two great podcast series.

And you can find another really nice graphic animation showing how the continents (and London in particular if you want) moved & morphed over time at:

Comments

Post a Comment

You can leave a message here or email me :

mail@mickbeaman.co.uk